The initial stages of diamond polishing

It perhaps seems astonishing that the first steps in the diamond polishing craft were taken in the late middle age, about 1350 A.D. Actually, dating the beginning of the diamond polishing skill back to the 14th century is wrong in any case. In India, diamonds were“polished” much earlier than that. But then, it did not involve the faceting and shaping of a rough diamond, as we know it today. In Europe, the attraction of polishing diamonds was born from a desire to discover new gemstones, but this was not the incentive in India. India had an abundance of precious stones. Kashmir had the best sapphires, Burma the best rubies and the whole of India was full of precious stone deposits of all kinds. All these precious stones could be processed and polished into jewels. But there was something different about the diamond. It ranked much above all other precious stones. To polish it into a jewel would be to degrade it. Moreover, a well-shaped rough diamond octahedron was of so much more value than any gemstone, that nobody had tried to convert it into a jewel. In addition to this, it was not as easy to process a diamond as it was to process another precious stone, since it is the hardest material known to man. The stimulus to process a rough diamond in India arose only and only out of the desire to remove any flaws in an “almost perfect” stone, for instance, if an octahedron has the customary triangular or pentagonal relief figures on one or several of its eight facets

Perfect octahedron

octahedron with triangular relief-marks on the surface

The ancient Indian scripture Ratnapriksa from the 5th century says: “the diamond flawed with even extremely small, barely perceptible damages is only worth one-tenth of the value or even less. The diamond, large or small, which has several noticeable flaws is not even worth a hundredth of the value.”A visible inclusion inside the stone could naturally not be corrected. But it was easier to polish off any relief figures on the surface of the stone. The only problem was that there was no material that was harder than the diamond. What could be used to polish away such defects? The only material for this was naturally again the diamond. Since the increase in value of even a small diamond was enormous if a flaw was polished away, the incentive was naturally high. Even if a worker took ten years to polish away a single, tiny flaw in a one-carat stone, it was still good enough. And thus, diamonds were polished using diamonds very early on. A simple device was used for this purpose and this was still in use in the Panna region till the last century. The Panna region is the only place in India where rough diamonds can still be found.

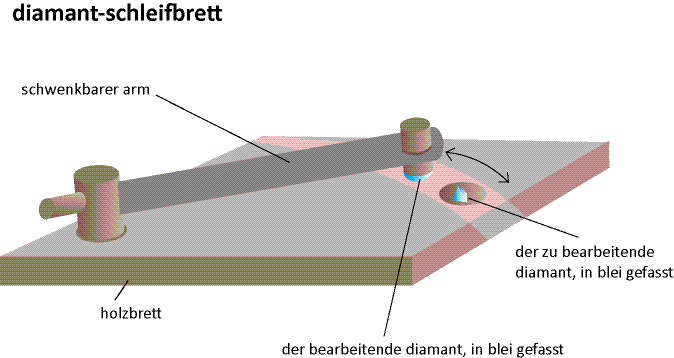

The diamond polishing board

The diamond polishing board is a simple instrument – usually smaller than a DIN A-4 sheet. A wooden arm grinds one diamond to and fro on another diamond. If the two diamonds are rubbed against each other for a sufficient amount of time, both of them polish each other. Eventually, in this method, the diamond polishers of ancient India realised that their method sometimes lead to a quick result but at other times, to nothing. With some observation, the Indians stumbled upon the big secret: the diamond in itself, is of varying hardness! If both the octahedron and the processing stone are fixed at a certain

position, the octahedron can be processed relatively specifically and effectively. This is because a diamond is up to ten times harder than the “soft” direction than when it is applied in the “hard”direction.

Diamond polishing board

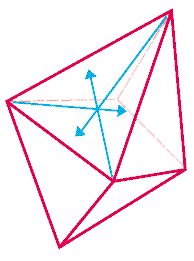

The soft directions in a diamond are always the directions from the tip of a triangle up to the centre of the opposite side, on the octahedron triangular facet. A diamond, in fact every diamond, has only a few polishing planes, and only a few polishing directions in every polishing plane. The polishing planes are:

a) the octahedron facet.- a triangular facet, which actually appears eight times in an octahedron. However, since two planes are always parallel, there are only four real polishing planes. This plane is called the Dzthree-point planedz, since it has three polishing directions

Octahedron facet

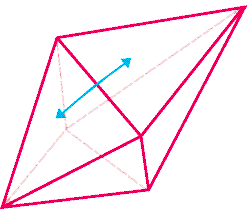

b) the octahedron edges.- twelve of these edges can be found in an octahedron. However, even here, two edges are always parallel. Therefore, there are altogether six polishing planes through the edges. There are two polishing direction each in these polishing planes, which run 90 degrees to the edge. Thus, these planes are called two-point planes

Octahedron edges

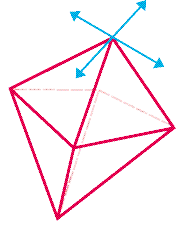

c) the octahedron points.- these are also called four-point planes, since there are four polishing directions here. The octahedron had six points. Since two respective points lie opposite each other, the octahedron has three so-called four-point polishing planes.

Octahedron points

Every diamond has the octahedron crystal structure, irrespective of its shape. Even if a rough diamond looks like a pile of scrambled eggs or a potato, it still has the crystal structure of an octahedron. And every rough diamond has four three-point polishing planes, six two-point polishing planes and three four-point polishing planes, irrespective of its shape or appearance. Thus, every diamond altogether has 4 x 3 + 6 x 2 + 3 x 4 = 36 soft polishing directions. All other directions, approximately 100,000 (360 x 360), are hard. A deviation of a few degrees from the actual polishing direction causes the hardness to increase to such an extent that the diamond can barely be polished any longer. The fact that this knowledge about the varying hardness of the diamond was discovered in Europe only in the 14th century was probably because this knowledge was kept secret, like no other. Similar to the art of mirror production in Venice in the middle ages or the art of glass production in ancient Egypt, diamond polishing in India was certainly also one of the best kept trade secrets. In any case, there are no written records pertaining to the art of diamond polishing in ancient India. Sometime, presumably in the late Middle Ages, diamonds began to be polished as jewels, even in India. In the beginning, only flat diamonds were polished to oval briolettes or to the so-called “rose-cut”.

The knowledge that diamonds can be processed came to Europe via India only in the 14th century. At that time, the diamond was more expensive than other jewels, but only because it was so expensive in India, and could only come from India. Since a rough diamond was very insignificant for the European way of life, there was hardly any interest in importing such a stone from India for a huge cost. And hence, there were only very few rough diamonds in the whole of Europe. Most of the naturalists who had talked about the diamond in their records (possibly including Plinius in Old Rome) had never ever seen a diamond. This is also evident from the fact that almost all European naturalist records about diamonds claim that the diamond would dissolve in the blood of a he-goat. If diamonds had really been available then, this superstition would have hardly lasted for one and a half thousand years among the scientists.

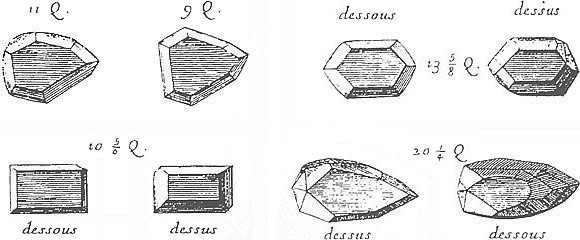

Rose cut diamonds

The diamond was well-known in the Roman Empire and had a prestigious position there as the most valuable object, but it was not very common. It was apparently handed over to a successor as a symbolic insignium of power, when an important post was conferred. Aelius Spartianus wrote in the 4th century:

“During the second expedition to Dacia, he (Traianus) made him (Hadrian) the commander-in-chief of the second Minervion legion (whose main stock location was located in present-day Bonn) and took him along. At that time, many of his outstanding deeds brought him fame. Thus, Traianus passed on the diamond, which he had received from Nerva and which was a symbol for succession.”

In Europe, the art of polishing diamonds probably had its origins in one of the most technically advanced cities of Europe, Nuremberg. Nuremberg was much more superior as compared to the other European cities, with its trade guilds and its citizens’ drive for research.

Thus, it was not only the extremely famous gingerbread, but also tin or pencils for instance, which were produced in Nuremberg.

However, historians often claim that the art of polishing diamonds began in Paris or was principally developed in Paris, as far as Europe was concerned. But this is not entirely true. The first written reference to diamond polishing in Europe comes from Nuremberg. For instance, Nuremberg had a “guild” of diamond polishers in as early as 1375. There are no written records available, pertaining to diamond polishing activities from Paris or any other European city as early as this.

Diamond polishing obtained a completely new dimension with the option of processing rough diamonds into gemstones. At that time, there was virtually no limit to the pomposity and prestige requirements of European aristocratic families. And thus, Paris was naturally one of the most lucrative locations for the sale of new products. Hence, it is no surprise that the first written record that alludes to diamond polishing in Paris, mentions a diamond polisher called “Herman”. The record dates back to 1407. It evidently pertained to a diamond polisher from Nuremberg, who moved to Paris got ahead in his big career over there.

Until then, diamond polishing was still a skill that took place without a polishing wheel. By then, the diamond polishing board from India had been replaced by advanced technology in Nuremberg. A tabletop was “impregnated” with diamond powder and the diamonds to be polished were grinded on it. This method was elaborate and tedious, but resulted in success. In principle, this method does not differ from the procedure used today. The diamond crystals, which are scattered in different polishing directions, polish the diamonds grinding in the soft direction on the tabletop and create a facet.

The Flemish diamond polisher Lodewyk Van Berquem from Bruges made an extremely decisive breakthrough in the art of polishing. He discovered that diamonds could be polished with their own diamond dust and developed the diamond grinding disc. And since then, i.e. the second half of the 15th century, polishing technology has barely undergone any changes. What came along much later was the sawing of diamonds and the grinding of the girdle. But diamond polishing or faceting technology is still the same today, as it was at the end of the 15th century.